Sable: To glide, and perchance, to vibe

In literature, an ellipsis is a gap in the action of the story where the reader jumps in and fills up the blank space on their own, using whatever context the writer gave them. It’s what happens within the brackets, the stuff that needs to stay unspoken so you don’t lose focus on what’s essential.

Sable makes a game out of the ellipsis. Imagine a childhood, from cradle to adolescence, and then imagine an adult life, complete with family, vocation, and aging. Then think about the bridge in between those things, the awkwardness of teen years and unpaid internships. That’s the space Sable holds for ten or twelve hours and inviting you into the easy openness of wide horizons and impossible choices.

Video games live and die by the stakes they set up for their players. Growth, leveling up, and exploration are all labor - and games tend to embrace that idea. Think of how hard some games are to beat, the sweat and tears they demand as you puzzle their spaces out, come up with new tactics for ever harder bosses. A game without stakes is a game without challenge, and a game without challenge is like a story without action - why push forward at all?

Sable doesn’t care if you feel the need to push. Instead, Sable invites you to linger, to feel things out, maybe, perchance, to vibe. The speeder bike given to the game’s protagonist in the prologue can go fast, sure, and technically, it has “stats” and “upgrades” to play with. But Sable doesn’t care very much how invested you are in your bike’s acceleration or durability. Instead, it cares if you remember your bike’s name, Simoon. It asks you if you’re able to hear it speaking in its machine language. It reminds you, by the time your adventure closes ,that Simoon is only with you for a time, a companion on your sojourn that will move on to someone else as they embark on their Gliding.

And that’s the mood. Everything you do in Sable is a passing moment, something to savor while you have it before letting it go forever. This is one of the few games I’ve played where the timing of its end is left almost wholly up to you. Sure, you could stretch it out, refusing to come home and choose a mask until the end of time, but the world of Sable has room for that. Leaving Sable behind to glide forever on the wastes isn’t subversion, it isn’t following the traffic laws in Grand Theft Auto. The game says, take all the time you need, as much to the player as to the protagonist. Maybe Sable wants to glide for as long as she can, having grown attached to the romance of wandering rather than the home base of a vocation. Putting the game down and refusing to finish Sable is an ending that Sable anticipates. I felt, playing this thing, that if I walked away from the game without ever choosing a profession and seeing the game’s end, I would have finished just the same, leaving Sable to simply live out her time on the dunes, an eternal dilettante in a world of dedicated artisans.

I did eventually make a choice, returning to the Ibex home encampment and donning the mask of the Shade of Eccrius, choosing to live out her career as a vigilante in the name of empathy and care. This did not trigger a good ending or a bad ending, simply a closing of the parentheses, an end to our wanderings, and a return for me to the world I’d left behind for a while.

Games are always an invitation into ellipsis. When you play a game you choose to divert your energies into a pair of brackets - come live for a while somewhere else with different faces and new horizons. Sable takes that invitation into the parenthetical one step further and stages it as the game’s very subject. I loved this game because it never asked me to optimize my path or to think tactically about its environments and denizens. Instead it asked me to stretch out and feel the boundaries of my body brush up against the cliffs, sands, and derelicts of its wastes, jungles, and canyons. Not to achieve anything, not to save the planet, not even to make friends, but simply to feel what it is like to detour away from the action, to pause, to notice.

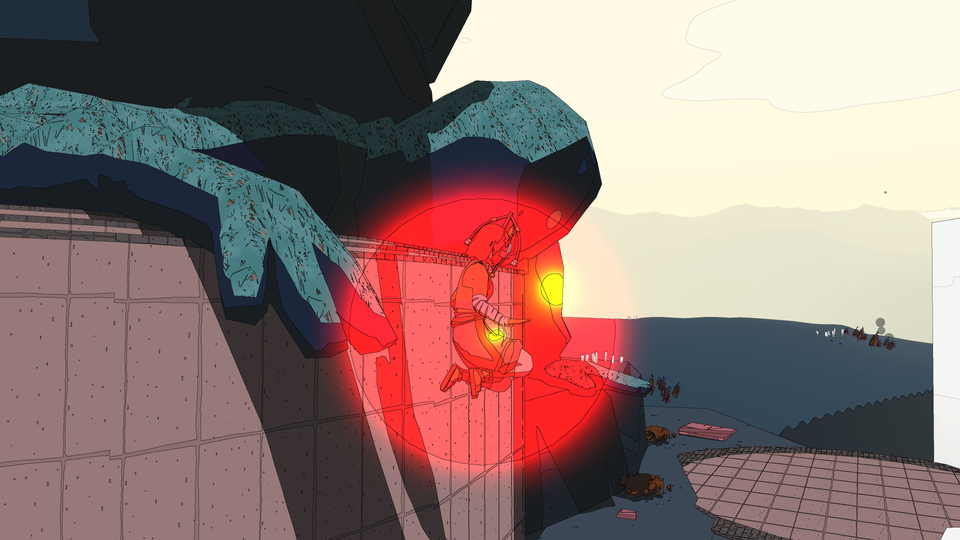

Tucked away in the far southeastern corner of Sable’s territory is a giant, ruined planetarium. There, if you are clever enough to find a way in, you’ll encounter a model of a solar system, and Sable will remark on each planet as you bring it into view. She muses about the gods of her society and their relation to the heavens, the strange beauty of twinned moons, and her gratitude for the warmth of their sun. Then, when you pull her planet up, she describes it as a planet sheltered inside a bubble. Her world is encased, surrounded, by an impenetrable orange-ish aura that Sable knows protects her from the barrage of radiation and meteors careening through space. But seen from this perspective, as a tiny ball within a shroud, she wonders for the first time if that protective shield isn’t also a prison. An eternal ellipsis from which she can never escape. She brushes the notion off, quickly understanding that even if there’s truth to the idea, it would rob her of the joy of gliding.

When Sable glides, she does so within a protective bubble as well. It shelters her from the world around her, a gift from the gods that lets her sail safely from cliffside to mesa, cartography balloon to moored wreckage. This is the magic of Sable, the game - it’s a bubble for you to hop inside, a parenthesis for you to pause and be held while you drift, simple and deliberate.

And so, you glide.

If you enjoyed this piece and want to see more like it, delivered weekly to your inbox, go ahead and click that subscribe button in the bottom right. We'd love it if you stuck around.

Member discussion